We didn’t start the night out talking about what makes a risky investment.

But, mid-match, while sprinting around the tennis court like a frantic mother-hen trying to corral her chicks, (or, in this case, little yellow balls), my partner paused from swatting balls at me like the 50-year-old reincarnation of Roger Federer and said, “Ya know, your post on Facebook today was really only speaking to people like yourself.”

The post in question? A quote from Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s classic Antifragile.

“It is completely wrong to use the calculus of benefits without including the probability of failure.”

The rest of the post was decidedly “investment” focused, which is likely where most people got lost, but that’s unfortunate, because the underlying message is pertinent to all aspects of life.

“Most people aren’t comfortable with taking your level of risk,” Brandon continued. “If anything, most people suffer from the opposite problem. They’re too loss-averse!”

A fascinating insight and reminder that most people don’t spend all day thinking about risk and trying to understand what it really entails.

Brandon saw me as a risk-taker.

Strange…’cause I would’ve said the same thing about him.

What’s a Little Risky Investment Anyhow?

On the one hand, Brandon saw me as being the risky investor because of my focus on multifamily properties.

Real estate (especially if you lived through 2008) often carries the label of risky in the mind of the general public.

Historically there wasn’t a ton of information on how to invest in real estate (multifamily specifically), and so it maintained an aura of mystique and confusion.

Also, it wasn’t terribly easy to invest in multifamily real estate.

If you wanted to participate in a syndication, of the sort we do at Invictus Multifamily, you had to know somebody actively doing the thing, and the chances of coming across that person were slim to none.

That changed with the passing of the 2012 JOBS Act, which opened more avenues for marketing these private placements. That, coupled with the Internet, as it’s wont to do, has brushed aside the gatekeepers guarding the doors of education and access, making multifamily more readily available to all.

On the other hand, I saw Brandon as the riskier investor.

So what’s Brandon’s investment-style?

The same as most peoples.

Most people invest for retirement in a 401(k) or IRA or some other tax-advantaged account they can’t touch for many years.

And sure, the tax advantages of these accounts coupled with a potential employer match on the 401(k) makes these, in theory, not the most risky investment vehicles around. The problem is where those vehicles are parked.

That is, predominately, the stock market.

Have you ever stopped to wonder, “Why is that?”

I put that question to Brandon and his response was telling, “Because that’s what everybody says you’re supposed to do.” This line of reasoning calls to mind every mother’s perennial question, “If everybody else jumped off a bridge, would you?”

It depends on the reason they jumped, I suppose, but that’s a conversation between you and your mother.

In this case, moms got a good point.

The problem with following the masses is that it presumes the masses know what the heck they’re doing.

Ask around, especially when it comes to investing, and you’ll quickly realize most people don’t know what they’re doing or why they’re doing it. When pressed, they typically regurgitate something along the lines of, “That’s what they tell you to do”, ala Brandon.

And here’s where we arrive at the critical crossroad:

Who is this they spreading the advice of investing for retirement in stocks and bonds and index funds?

They are investment advisers, financial planners, stockbrokers, and the general media.

The next important question to ask is:

Why are they pushing stock market-related investment vehicles so hard?

To answer most questions in life where more than one individual is involved, we have to understand the other person’s incentives.

What are they getting out of this?

An immense amount of money gets pumped into marketing the stock market. Which makes sense, ‘cause there’s big money to be there…but not by the people you think.

The people reaping the largest rewards from the stock market are the gatekeepers, custodians, and all those countless individuals making a fee off managing your investment regardless of how that investment performs.

They lack skin-in-the-game (another fantastic book from Taleb).

You might not think this is a big problem. After all, you’ve been putting money into your 401(k) and it’s generally earned money for the past decade (outside of a few major hiccups). So what’s the issue?

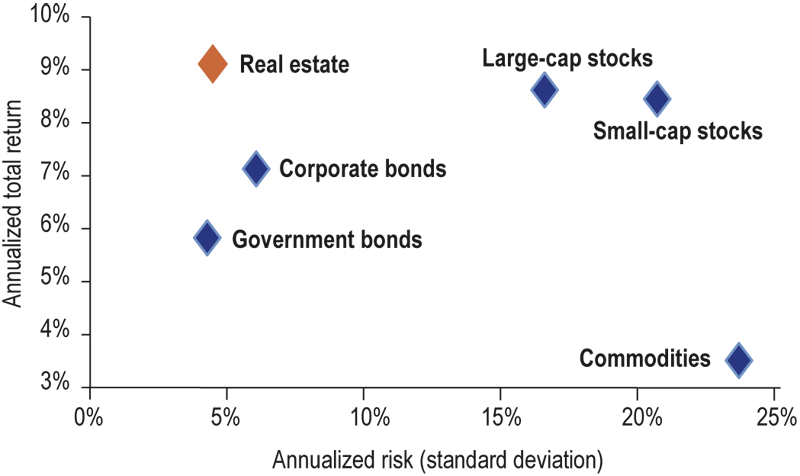

Here, let’s use a graph to paint a better picture than words ever could.

Bring the Data and Show Me The Risky Investment

Thomson Reuters performed a 20-year study of 6 major investment vehicles. They plotted these vehicles against Annualized Total Return and Annualized Risk.

Risk can be defined in a lot of ways, and we’re going to cycle back because the risk side of the equation is the most interesting for the purposes of this article, but before we do, let’s understand what the graph is trying to say.

Typical investing theory suggests the Riskier an investment, the higher the expected Returns.

This makes sense. If presented with two opportunities projecting similar returns, but one investment is twice as risky, you would select the safer/stabler option.

With this in mind, it’s not surprising to see Stocks (both large and cap) are pushed well out on the right (high risk), and high on the Y-axis (high returns). By contrast, Bonds (both corporate and government) are well to the left (low risk), but they also don’t peak as high (low returns).

Now, let’s consider the little dot sitting in the unicorn position of being high on the Y-axis (high returns) and low on the X-axis (low risk): Real Estate.

This asset has one of the lowest annualized risk rates (comparable to government bond) and one of the highest annualized total return (greater than even the ever-volatile Large Cap Stocks.

For ourselves, we seek the best Risk-Adjusted-Returns possible. Which means pursuing the upside while simultaneously managing potential downside.

The above-graph suggests there is a clear winner where Risk-Adjusted-Returns are concerned, which raises a few questions:

- First, how does real estate realize such outsized returns in relation to its risk profile?

- Second, why don’t more people know about it?

- And third, but what about the real estate crash of 2008?

Let’s tackle these questions in order.

It makes sense to compare returns and risk profiles of real estate with stock and bonds as these are both investment vehicles, but it is a bit like comparing apples-to-oranges.

Commercial real estate functions as a business (much as do the companies underlying the stock market). The issue arises with how valuations are derived and equities exchanged.

Commercial real estate has a very defined formula for calculating a building’s worth which is:

Net Operating Income / Capitalization Rate = Building’s Value.

This is the formula banks and other investors utilize to establish a properties worth.

There is no such formula in the stock market where participants often buy and sell shares of a company capriciously, based more on the trending news cycle or gut feeling than on any solid underlying formulation.

Take yourself, for example, perhaps you own some Apple or Tesla stock.

Do you really know how the price of that stock was calculated?

Did you make a buy or sell decision-based on those fundamentals of price earning ratios or free cash flow or any of the other innumerable ways one could calculate value?

Or did you buy it because everybody has an Apple phone in their pocket and you think Elon Musk is dreamy?

Okay, those are my reasons, yours might be different.

Perhaps your reasons are in-fact based on a solid understanding of the underlying financials. If so, great! But that means you’re in the minority.

Which explains why stock prices can fluctuate so wildly based on the CEO smoking weed with Joe Rogan.

That, in my book, is a risky investment.

Many of the market forces at play in establishing a stock price are exacerbated by how easy it is to buy and sell these stocks multiple times over in a single minute.

Commercial real estate, by comparison, is fairly illiquid, meaning you can’t just buy and sell on a whim. This results in less volatility in the short-term.

If all this is true, it begs the question:

Why don’t more people know they can invest privately in real estate?

Again, follow the money.

Wall Street spends a fortune to keep you locked into the market, because that’s where they stand to benefit. If you place your money in a private asset, they reap none of the benefits of your money.

In the not-too-distant past if you wanted to participate in a real estate syndication, you had to 1) be pretty affluent and 2) you had to know a guy or gal already doing the thing.

A lot of this changed in 2014 with the passing of the JOBS Act, which tore down many of the barriers to entry and ushered in a new wave of potential investors.

This wave of momentum created a “bringing the fire off the mountain” moment within the syndication space as educational resources flooded the market illuminating the potential of this powerful investment vehicle.

Now, what was once an obscure, little-understood, and difficult to access opportunity, has become a popular, simple, and readily-available alternative to the stock market.

In the fight between Main Street and Wall Street, the tides are turning.

“But,” you might ask, “what about 2008?”

Many people, when they think about real estate investing, think about the financial crisis, which was, at its core, a real estate problem. Right?

Well, yes and no.

Real estate is a broad category encompassing everything from single family homes to multifamily apartments to storage facilities to hotels to retail space to… you get the idea.

A lot of things qualify as real estate.

Importantly, though, not all real estate is created equal.

Different niches perform, well, differently.

The 2008 financial crisis was a problem of the single family home niche. Individuals bought primary residences they simply couldn’t afford.

When the market crashed and people lost their jobs, suddenly those people flying too close to the sun, got burned.

Now, it’s important to realize the single family market is fundamentally different than the Commercial Real Estate (or, more specifically, Multifamily Real Estate) market we’re discussing here.

If we back-test commercial real estate assets to see how they performed during 2008, we find the delinquency rate was only 1.2% versus the 20% of the single-family market.

Of course, commercial real estate took some hits during that period (slow rent growth, higher vacancy, etc…), but the vast majority of operators managed to meet their debt obligations meaning the properties weathered the storm.

And what a storm that was.

This is why investors speak so highly about the recession-resistant nature of multifamily assets.

The Devil You Know

The Risky Investment You Can’t Ignore

Most people invest for retirement in the stock market because for it’s more comfortable taking the devil you know versus the one you don’t.

I get it, real estate seems spooky.

There are plenty of stories of Uncle Jerry losing everything in a real estate deal gone bad. Plenty of other stories about tenant nightmares. Not to mention you’re a busy working professional who doesn’t have the time, energy, nor desire to be on call 24-7 dealing with tenants, toilets, and trash.

Thankfully, if you want to participate in real estate and enjoy the full suite of benefits (cashflow, appreciation, tax-breaks), you don’t have to be an active investor managing your own portfolio.

Apartment syndications are great because they allow passive investors the opportunity to partner with experienced operators who handle all the active work in finding, acquiring, managing, and eventually exiting the asset.

Passive investing in apartment syndications makes a lot of sense, but for most people, it’s new and scary and can seem like a risky investment. That’s why we created a Quickstart Guide to Passive Investing In Multifamily that you can grab for FREE.

This 22-page guide will walk you through everything you need to know so you can jump into a syndication with complete peace of mind.

Risk Is All A Matter Of Perception

Returning to my buddy on the tennis court’s point, I understand how from the outside it appears investing in real estate is riskier than investing in the stock market.

So let’s consider risk for a moment.

Investment risk is defined as:

The chance that an outcome or investment’s actual gains will differ from an expected outcome or return.

Volatility plays an enormous role in calculating an investment vehicle’s risk profile.

Stocks and bonds are perfect illustrations of this.

Government Bonds are relatively stable instruments supported by the government itself. When you pick up a bond at 3% over 10 years, you can be fairly certain you’re going to receive 3% over those 10 years.

Stocks, on the other hand, are far more volatile. Cashing out the month before the world went into Covid-lockdown earned you a distinctly different return than if you’d waited until a month into the lockdown (around 20% different!).

If you’ve ridden the stock market rollercoaster, you know exactly what it feels like to watch from the sidelines as your nest egg gets slashed into ribbons.

It’s a horrible feeling, but one you don’t have to endure. There are alternatives.

Commercial Real Estate through that same lockdown period performed as well if not better than it had previously. Strong rent collections across the country lead to consistent cash flow and stable property valuations.

It’s best to think of Real Estate like an ocean liner (or a Jumbo Jet). It takes a long time to turn around. The impacts of frothy markets take a while to be realized, which gives us times to react and prepare.

Something you simply can’t do in the stock market.

Risk is a highly personal thing. Some might look at me and think, “That guy has a high tolerance for risk.” Then again, I might look at you and think the same thing.

For me, risk is putting your money into an investment vehicle you don’t understand and have zero control over.

Not thinking for yourself and taking control over your financial future by understanding and consciously deciding where to invest your money is…well, to me, that is the ultimate risky investment.